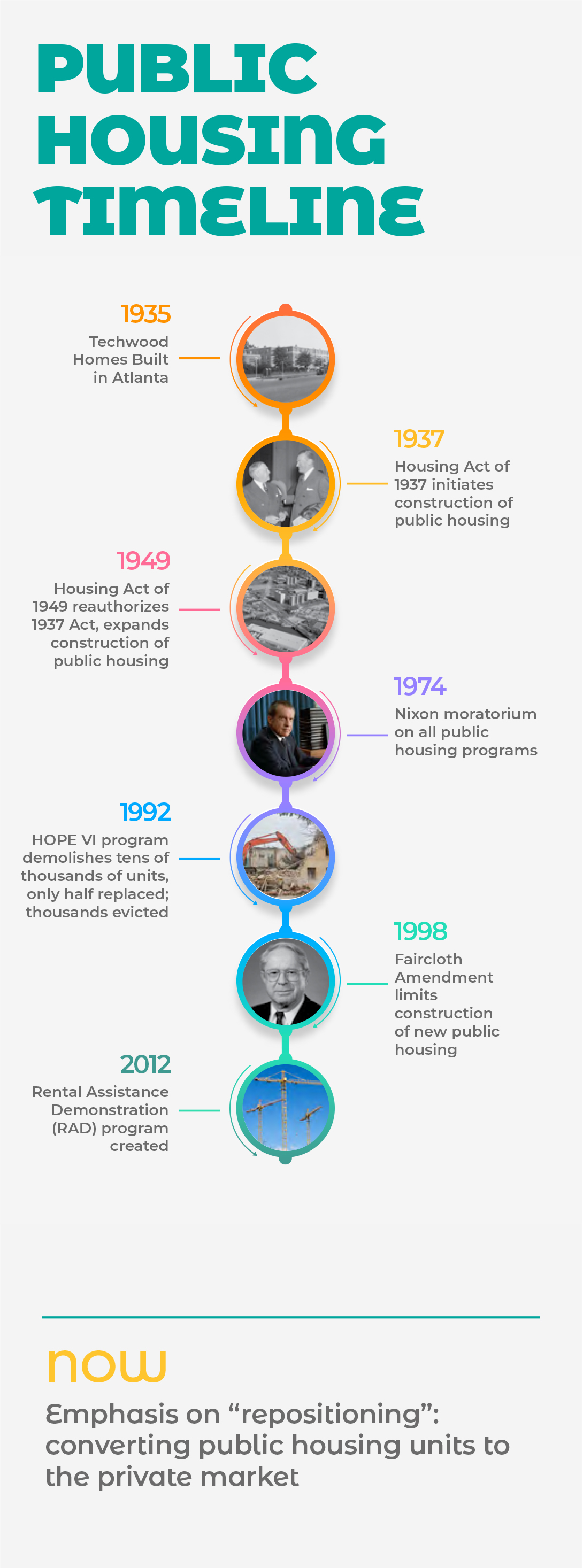

HOW DID WE GET HERE?

A QUICK REVIEW OF PUBLIC HOUSING HISTORY: A New Deal Program with Segregationist Beginnings

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the Housing Act of 1949, which significantly increased the number of public housing agencies (PHAs) and led to more widespread construction of the public housing stock we see today. The following is a brief history of public housing.

Public housing is the oldest and, until recently, largest housing subsidy program in the country. Today’s 1.1 million units of public housing, operated by over 3,000 local public housing agencies, serve 2.2 million residents. Not to be confused with other housing subsidy programs, public housing is housing stock that is owned by HUD and administered by local PHAs.

The federal public housing program started as part of the Housing Act of 1937, passed during the New Deal. First intended to be a jobs program and slums-clearing effort, public housing was the result of powerful grassroots organizing. Social justice advocates like Catherine Bauer of the Regional Planning Association of America mobilized massive public support for the movement for government-sponsored housing, i.e., public housing.

In his book The Color of Law, Richard Rothstein explains the intensely segregationist beginnings of public housing. The federal government helped local governments carry out their housing segregation policies or did little to stop them. The Public Works Administration (PWA), created under the New Deal to address the country’s housing and infrastructure needs, constructed Techwood Homes in Atlanta, GA, in 1935 as the first federal public housing project. The project evicted hundreds of black families to create a 604-unit, whites-only neighborhood. That same year the Supreme Court ruled the federal government lacked authority to seize property through eminent domain – but local PHAs did have this authority, allowing them to act without proper oversight regarding the placement of public housing.

The federal government’s practice of creating segregated public housing persisted throughout the second half of the 1900s. In 1954, shortly after the federal government expanded the public housing program under the Housing Act of 1949, the Supreme Court handed down a landmark decision invalidating “separate but equal” public education. Housing and Home Finance Agency (HHFA) General Counsel Berchmans Fitzpatrick stated the decision did not apply to housing. And one year later the Eisenhower administration ended the policy that black and white communities should receive equal quality housing.

While public housing production increased in the post-war period, segregated public housing construction persisted throughout the 60s and 70s and cemented deeply segregated public housing across the country. In 1984, the Dallas Morning News visited 47 metropolitan areas and found nearly all public housing tenants in those areas were segregated by race, and white housing projects had better amenities.

After passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, public housing would no longer be a tool for advancing segregation. Just six years later the federal government started a steady withdrawal of support for public housing beginning with President Nixon’s moratorium on housing spending in 1974. There has been no significant expansion of public housing since then, as federal housing subsidies shifted to housing vouchers.

HOPE VI

Despite the consistent attempts to undermine public housing and media portrayals of dilapidated, crime-riddled tower buildings — the program remains popular among its residents. Alex F. Schwartz notes in his book, Housing Policy and The United States: “Public housing is unpopular with everybody except those who live in it and those who are waiting to get in.” Indeed, so many people want to live in public housing that the wait lists are almost always years-long.

Steady underfunding and austerity cuts under President Reagan in the 80s led to the declining quality of public housing. In 1989, Congress created the National Commission on Severely Distressed Public Housing to survey the condition of the nation’s public housing. The Commission found only a small percentage, 6%, was “severely distressed.” Nevertheless Congress appropriated $600 million to the HOPE VI program, which was publicized as an “urban-renewal” effort to demolish distressed units and replace them with mixed-income housing.

The program resulted in an overcorrection for a program that really needed more funding and better management. Over 50,000 households were told they would be “temporarily” relocated, but fewer than half of them could return to their repaired homes and even fewer could afford the new mixed-income housing. Ultimately, HOPE VI left tens of thousands of public housing renters displaced and drastically decreased the public housing stock. HOPE VI was also the precursor to today’s “repositioning” effort.

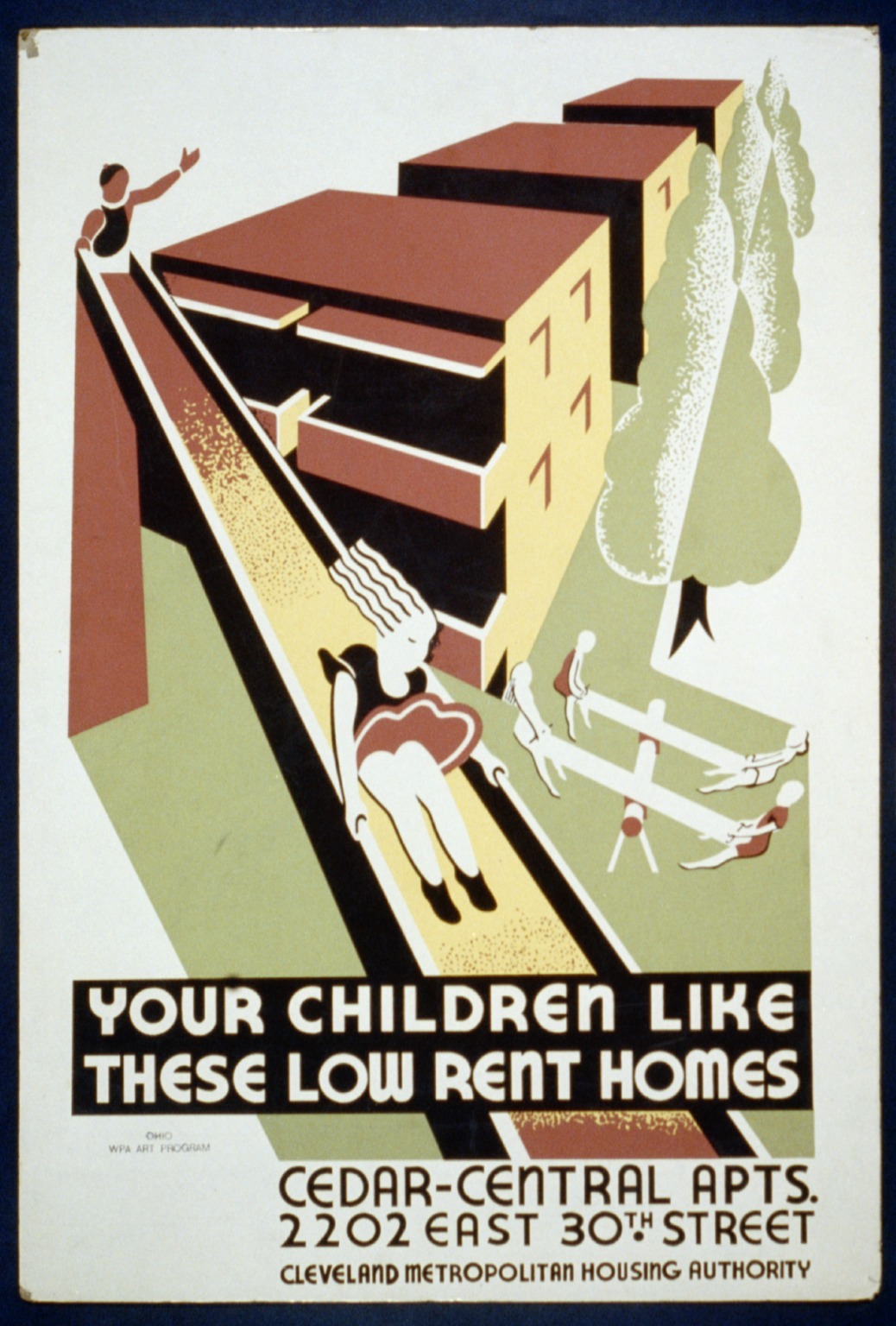

Work Projects Administration Poster Collection